Steve Bennett journeys to Gdansk, on the Baltic Coast of Poland, to discover the fascinating story behind Baltic Amber and how it is found.

For a long time I have wanted to make the short trip from the UK to Northern Poland to see how Baltic Amber is discovered and extracted, but it has always been a well-guarded secret of the locals of Gdansk. After a lengthy chat with my good friend Mariusz Gielo about how it would be a real benefit for the town if a proper documentary was made about their historical gemstone, he was able to convince Zbigniew Strzelczyk, the president of the Polish Chamber of Commerce for Amber, to organize a fully ‘doors open’ visit for us. Before we get to that, however, let me start with a little background on Amber - the gem known in Polish as Bursztynu.

At least 40 to 45 million years ago there was a huge forest in an area roughly where the Sambia Peninsula is today, around the coast with the Baltic Sea. The Amber, which of course is fossilised tree sap, would have been left behind as the forest decayed. As the gem is so light in weight, even floating in saltwater, the Amber was picked up by streams and rivers, and flowed south towards Poland. Most of the Amber discovered inland has been unearthed in sedimentary rock, which suggests that the gem was transported in very shallow waters. In fact, the depth of the Baltic Sea is still very shallow.

We believe that most of the Amber found here started its journey from the deltas of the Sambia Peninsula at some point in the last million years. During that time, there have been at least four periods where glaciers have formed and nobody is exactly sure which one helped the Amber to migrate to Poland. Some believe that much of the Baltic Amber travelled approximately 20,000 years ago, when a huge glacier pushed south, almost to the southern tip of Poland, carrying with it ancient Amber which it then deposited in various locations across the country. Around 10,000 years ago, this glacier receded and as it melted it created the Baltic Sea. At first this was landlocked, but by the time the glacier had completely melted, it had risen to connect to the Atlantic Ocean. This, we believe, happened just 6,000 years ago.

Interestingly, prior to merging with the Atlantic, the Baltic Sea would have been freshwater. Therefore, as quality Amber is just slightly heavier than fresh water, it would at this stage have bounced merrily along the sea bed, submerged. But as soon as the oceans connected, the saltwater of the Atlantic ocean would have flooded into the Baltic Sea and the Amber would have begun to float, and travel faster and faster. So the Amber that we find on the Baltic shore today is most likely younger than that which is found inland, which was pushed there by the glacier. Of course these pieces may have just been the last to leave home, or maybe they got stuck somewhere along their way. For me, the uncertainty surrounding this gem only adds to its mystique.

Some believe that much of the Baltic Amber travelled approximately 20,000 years ago, when a huge glacier pushed south, almost to the southern tip of Poland.

Amber was formed inside large trees. It dripped from wounds and cuts in the bark, as well as forming as pockets inside the trunk itself. The trees used the resin as an antibiotic and like an effective ‘sticky plaster’ for their wounds. Baltic Amber in fact possesses between 3% to 8% of succinic acid, which these days is used as a therapeutic substance, among other uses. The word ‘succinic’ is derived from the Latin ‘succinum’, which simply means Amber. But what species of tree were they? Pliny the Elder wrote that the gem was the juice of a tree called sucuc. I am always fascinated how Pliny, 2,000 years ago, was so amazingly accurate in many of his writings. Pliny suggested that the tree was either a pine or a cedar. Whilst many scientists since have proposed other species, if I was a betting man, and with Pliny’s amazing track record, I would go along with his writings.

What nobody knows is whether the resin was always present in the trees, or whether it increased significantly due to some geological event. It’s possible that there was a sudden rise in temperature caused by a volcano that effectively caused the trees to create abundant resin.

How does the resin become so hard and so durable? Well, over a long period of time it begins to fossilise. The more the inherent moisture and oxygen evaporates over time, the harder the gem becomes. But one of the biggest mysteries of Amber is its toughness. On the Mohs scale it only registers between 2 and 3, yet the gem is one of the toughest gems of all. Considering its journey from the Baltic Sea, via river beds, through ice ages and glaciers, with many pieces tumbled thousands and thousands of times by the biggest forces in nature, the gem repeatedly resists all challenges thrown before it. I have asked many a gemologist to explain why this is the case and now I have asked possibly the world’s leading Amber expert, Zbigniew. Even he can’t give a scientific explanation of how Amber defies the normal rules of durability.

So, to our trip. Our first day would comprise a little sightseeing around the world capital of Amber, Gdansk. The entire city is consumed by the gemstone. It is estimated that over 30,000 people (almost 10% of its population) are employed either in the Amber trade or in supply to it! Gdansk was virtually flattened during World War II. Luckily however, the city’s planning department had keep meticulous plans and records of all of the buildings and shortly after the war had finished, Gdansk was rebuilt brick by brick to virtually an exact replica of its former self. It is such a beautiful city with its thin, tall buildings and winding waterways giving it an appearance not dissimilar to Amsterdam. We visited St Mary’s Church, the world’s largest brick built church, and we dragged our camera equipment up its 400 steps to film the view of the city from its roof.

It is estimated that over 30,000 people in Gdansk are employed either in the Amber trade or in supply to it!

The following day we were up at the crack of dawn to go with Zbigniew to the tiny island of Sobiszewska where, for over 43 years, he has fished for Amber. Zbigniew explained that as the sea was so shallow, during a storm Amber can get dislodged from the seabed and will drift towards the shore. Day or night, if it is windy, he can find himself battling with two or three hundred other gem hunters, all looking for Amber. Wearing specially designed wellington boots that come all the way up to his hips, we followed him along the beach to the water's edge. After a few minutes of watching the waves roll in, he decided where he was going to fish. On a cold still morning like the day of our visit, he faced no competition and the deserted beach was all ours.

After what felt like hours watching him comb the small waves as they lapped against the shore, he eventually found a small piece. He called me over and in his very next attempt found a second piece. But that was it. His luck had run out and he had to get back to his office. Before we left the beach, Zbigniew discovered a line of seaweed and shells that must have been washed up by the morning tide. He gestured to me that I should begin to sort through it and in no time at all I had found half a dozen tiny pieces of brightly shining Amber, one piece of which I was adamant was just about large enough to be cut. But just as a fisherman will toss an accidentally caught baby fish back into the ocean, he returned the Amber gem back to the sea, as if to say it was too small to even consider cutting.

Next we moved inland to visit a family that had obtained the rights from the local council to mine Amber in a field. Mr Dyszka has been prospecting for Amber since 1976 and today, along with his sons, they were using a method of mining that I had never seen before. The location was about 1km from the shore, and here the sand had been replaced by soil. The belt of Amber sits about 10 metres below the surface, but rather than bring in heavy machinery, they use a technique that has been honed over several generations.

One of the clauses in their mining contract, quite rightly, instructs that after mining is exhausted, they must return the land to it’s former state and therefore they first carefully remove the grass and the topsoil and put it to one side. Then they take thin sheets of metal and create a circle some five metres in diameter. They drive the sheets into the soil, to create what looks like a giant cookie cutter. Next they fire up their generator and pump water through a giant fire engine-like hose. They fix this to a long pole and use the pressure of the water to drive the pole into the soil. This then causes the soil to circulate within the cookie cutter, a bit like a giant washing machine, and Amber from within starts to rise to the surface where it is then fished out. It takes around 10 days of hard graft to circulate the soil until they are sure they have maximised the spot. Towards the end of that period, the father goes off and prospects the field trying to decide where next to try and uncover some Amber.

I asked Mr Dyszka how he prospected and he said that he didn’t use geologists, but instead just spent days drilling tiny bore holes until he discovered a piece. He told me a wonderful story of how in the days before the war, local Amber miners would watch birds in the field and from their behavior could accurately identify where to dig. Sadly their learnings were never passed on and the skill has died out. For a while there was also a gentleman who could tell from how the morning mist behaved, where to dig and find Amber. He told me that both of these methods had something to do with the heat that Amber throws off, but that they were so subtle that he was unable to master the technique, so for 35 years he had resorted to the more common practice of drilling test holes.

In the days before the war, local Amber miners would watch birds in the field and from their behavior could accurately identify where to dig.

Back in Gdansk we visited Zbigniew’s workshop. It reminded me of Glenn Lehrer’s hive of activity, as they are both artisans tucked away at the back of their retail stores creating wonderful pieces of art from natural gems. Whilst I have spent much of the last few years in gem cutting houses, there was something different about the atmosphere here - the smell! Every time Zbigniew touched the lapidary wheel with Amber, a cloud of wonderful smells filled the room. I was amazed, I had never smelt a naturally perfumed gem before. On seeing my delight, Zbigniew said, “Watch this”, and he lit a blowtorch, handed me an off-cut of dark Amber and set fire to it. It burnt like a candle, but with an aroma that was very soothing and relaxing. Zbigniew explained that on a warm day, or even with the warmth of the hand, Amber can sometimes generate a pleasant scent. Zbigniew explained how Amber is effectively alive as it is still transforming internally. Unlike many other gems that will fade slowly if overexposed to the ultraviolet rays of the sun, lighter Amber pieces darken as they lose some of the oxygen trapped inside.

A few years back they discovered the remains of an old Amber jewellery workshop. Early man did not have the technology we have today and during the drilling process, which they used to perform with a drill made out of fish bones, many pieces of Amber would break during the process. Archeologists discovering the remains of the broken pieces, revealing in the process how the gem has been worn in jewellery in the Gdansk area for over 7,000 years.

In the local museum, we saw many wonderful artifacts and pieces of jewellery dating back centuries, but without doubt the highlight for me was seeing the Gdansk Lizard. Discovered in 1997, this piece of Amber contains the perfectly preserved remains of a young lizard that was entombed in its completely transparent Amber coffin over 40 million years ago. Some wonderfully detailed artifacts date back to the Wejherowo-Krotoszyn culture of the 8th century BC.

Amber doesn’t just fascinate gemologists, it engages and educates geologists, paleoentomologists, geographers, chemists, zoologists, botanists, archeologists, historians and even physicians. It is living nature and along with its beautiful appearance, its healing properties and its mystery and magic, Amber is surely one of the most fascinating unique gemstones created by nature.

At the end of our final day, over dinner, we discussed the folklore surrounding the gem, of which there are many stories. This is not surprising when you consider the gem has been worn as a talisman by the Ancient Greeks, the Romans and many Asian cultures. Ancient Greek mythology suggests that Amber was made of the tears shed into the mythical Eridanus river by the grieving sisters of Phaethon, who was thrown into the river by Zeus for joyriding in his father’s golden chariot. In China, some suggest Amber was the solidified soul of a Tiger and for early Christians, Amber demonstrated the presence of the Lord. When Viking goddess Freya wept after her husband was lost at sea, her tears fell onto a rock which turned to gold. For others, including native Americans, Amber represents the sun.

With its incredible history, radiant glow and unfathomable scarcity, Baltic Amber is surely one of Mother Nature’s most fascinating creations. You can learn more about this trip in our documentary above.

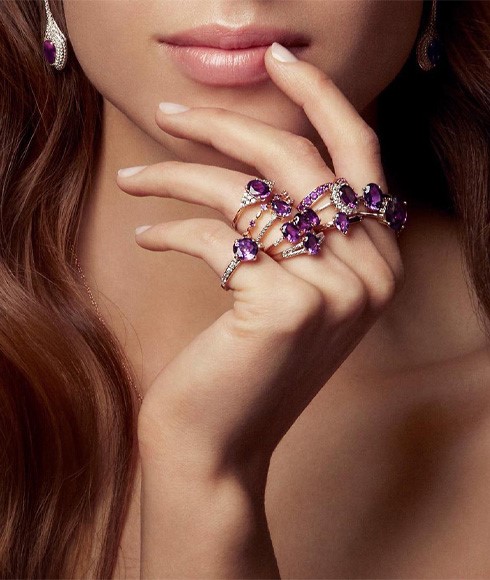

EXPLORE BALTIC AMBER JEWELLERY